There’s a Moral Here

I know I’m getting old because, as I was about to write this story, I thought of my 29-year-old self as a youngster.

This is not a fable, so I’m not going to make you wait until the end to hear the moral. The moral is: Never, ever, tell a glider pilot named Frenchie to scare the crap out of you.

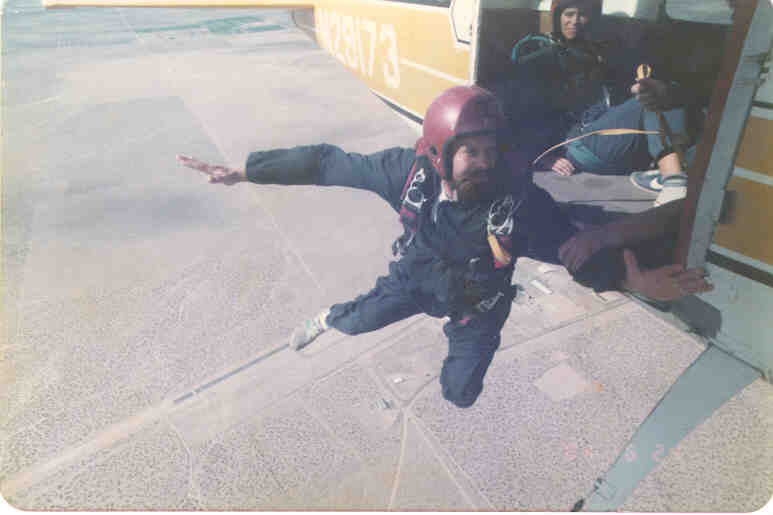

When I was twenty-nine I had a group of friends that were engineers. This was a naval base area, so depending which team they were on, either they were trying to build a missile that radar couldn’t detect, or they were trying to build a radar system that could detect stealth missiles. Anyway, 4 or 5 of us decided we wanted to cross jumping out of a plane off our bucket list. So we drove out into the Mojave Desert to small airstrip that, for the right price, would give you a two-hour ground school, take you up in the air, and let you fall.

But this story isn’t about jumping out of an airplane.

Trouble was, we got a late start and missed the beginning of the 8 am class, so we had a few hours to kill before the noon class started. The building next door had a sign on the roof that you could read from space: “Glider Lessons $20.” I decided to investigate. I paid my money and took my chances.

“Frenchie, you’re up,” said the guy behind the desk.

The guy was about 5’8” and built like he hit the gym daily. He had a square face, short parted hair and a neatly-trimmed full beard. In contrast, I was 6 foot, had a lumberjack beard, frizzy hair in a pony-tail and built like I ran daily. Frenchie put me in the front of the glider and he sat in the back.

I suppose I should tell you what the glider looked like. It was white. If you were to take a small private tow plane, remove the propeller, stretch the wings until they were twice as long, and then stretch the body to about 50% longer, it would look like that. The lead plane took off, towing us up to what Frenchie considered high enough, and released the tow cable. Then he instructed me that the stick and pedals were for steering, and told me to fly above the rocky slope and catch a thermal.

I managed to get the glider there, but couldn’t find a thermal. A thermal is a mass of rising hot air. It’s not like you can see it or hear it, or anything else. While I was thermal-hunting, Frenchie was getting more and more frustrated, yelling stuff like, “Left! Right! It’s right there!”

So I said, “Clearly I don’t know what I’m doing, so why don’t you fly the glider and try to scare the crap out of me?”

“What do you mean?” he said.

“Can you do a loop?” I asked.

“Nope,” he replied, “gliders aren’t built for that, but I can do a wing-over.”

It was difficult to converse because of the wind and a control panel between us.

So I just said, “okay.”

Now about this time I guess you are wondering what the heck a wing-over is. I was also pondering exactly what I had gotten myself into. We started out just going around in circles riding the thermal up. Way up. Then Frenchie pointed the glider out toward the desert and we started gaining speed. The faster we went, the more the glider vibrated. Suddenly we went straight up; then slowed until we stopped in mid-air.

For a moment my body floated. Then the seat harness tightened against my chest. We were falling straight backwards. The glider leaned to my left, rotating vertically, and next thing I knew, we were pointed straight down at the desert floor, plummeting faster and faster. Then Frenchie pulled back on the stick and the g-forces kicked in as he turned us to the horizontal. My body was compressed into the seat, my cheeks were flapping somewhere around my ears.

It took a while to glide back to the airstrip—I had no idea how long. Thankfully, by the time we landed, my shaking had subsided enough for me to climb out with a semblance of dignity.

I will say that jumping out of an airplane didn’t seem as scary as it had at 8 am.